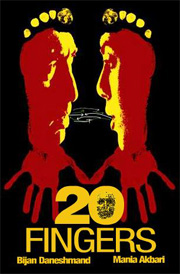

20 Fingers

Written and Directed by Mania Akbari

Produced by Bijan Daneshmand

With Mania Akbari and Bijan Daneshmand

BFI Mania Akbari Retrospective

After seeing Mania Akbari’s 20 Fingers at the BFI, who are presenting a retrospective of her impressive and innovative work, I joined friends and acquaintances in the bar. I was introduced to a budding novelist on a visit from the US who asked me in a frank manner: “So is it like that?” “Like what?” “Well as an Iranian man, is it like that?” I came up with my customary reply: “Why do you assume I’m a man?” She laughed. “And why do you think I represent Iranian-Man?”

In case you don’t know me, I am a man and Iranian born, but I always find it difficult to respond to generalisations like that. Surely we know that being a man or a woman is more complex than having a penis or a vagina in-between your legs and cultural reductionism is not my game. I grew up supporting Team Melli (Iranian National football team), watching Bruce Forsyth’s Generation Game on British TV and going to a French school. What kind of an Iranian does that make me? I thought of what Mania Akbari stated eloquently in her post-screening interview with Geoff Andrew, somewhat lost in translation to those who do not speak Farsi. To paraphrase, she said that her work is not particularly about men or about women, but about what takes place in-between.

The film starts with a back shot of Mania and Bijan sat in a car driving to an unknown destination. It’s night time. Mania speaks of games she played with her male cousin when they were children – Doctors and nurses, mummy and daddy – all with hints of childhood sexual frivolities. She speaks with an innocent nostalgic tone. Bijan asks precise questions: “How old were you when you did that? How old was your cousin? How long did it go on for? When did you stop?” He speaks with an interested if slightly nervous tone. Mania is baffled but obliging, she provides all the answers, water off a duck’s back. Occasionally she asks: “Where are we going?” Bijan answers: “Just a little bit further, there is a beautiful spot I want to show you.” It’s dark, the headlights are on, we can barely see the couple’s heads. Bijan stops the car. He turns off the headlights. The screen goes black. We hear Mania’s voice: “What are you doing? Are you crazy? Bijan?” she speaks with a gentle if surprised tone. “I had to check for myself”, says Bijan. “What shall I tell my mother, my sister? “ “I had to find out for myself.” He speaks with an affectionate tone.

In our mind, we can see Bijan’s hands exploring the film character Mania’s vagina, looking for the hymen, tearing it, feeling the blood and then perhaps penetrating it. “Are you crazy?” says Mania. She does not seem to stop him.

The in-between is beautifully established in this first sequence. The young couple’s fundamental relationship lies between a desire to roam freely and sexual exploration on the one hand , and a determination to preserve purity, to keep intimacy and sexuality within a private sphere, even at the expense of illegal sexual entry. Is it rape? Or is it an initiation of the relationship for years to come? Mania Akbari, however, does not make general statements about society. These are traits that come from the very specific situation of the fictional Mania and Bijan. It is repeated in various contexts. Riding a motorcycle in Tehran a few years later, with their toddler daughter precariously placed between them, they debate having another child. He wants one, she doesn’t. They talk, argue, shout. She jumps off the motorcycle and grabs a taxi. He follows them. She eventually gets out of the taxi and rejoins her partner on the bike, swearing at him whilst holding on to his waist. Later still whilst having a ride on a train, she tells him that she slept with a female friend. He throws her out of the train compartment into the corridor.

Throughout the film there is one constant. They remain together. They remain lovers. Mania Akbari explores different contexts at different times in the chronology of their relationship – the car, the motorcycle, the telecabine above the snow, the train, the car again – to show what preserves, fuels and protects the relationship. She provokes, he reacts, he provokes, she reacts.

In the very last scene, we see the couple on a small boat, on a lake, alone. Bijan says: “I really enjoyed myself. I had a good time. “ She confirms the sentiment. There is no one else, just the water, clean, pure, still. And then, the screen goes black, we hear the sound of the water and Bijan saying: “I feel good”, and we see in our mind, the manual search for purity, the tearing of the hymen, water and blood. In a masterstroke, Mania Akbari sends us home with the complex signs that construct the relationship between the two characters.

I say my goodbyes to the budding novelist, wishing her luck with her novel-waiting-to-be-published. As a parting shot I say: “If anything, I identify myself with the fictional Mania”. I turn to look for the real Mania in the bar.